|

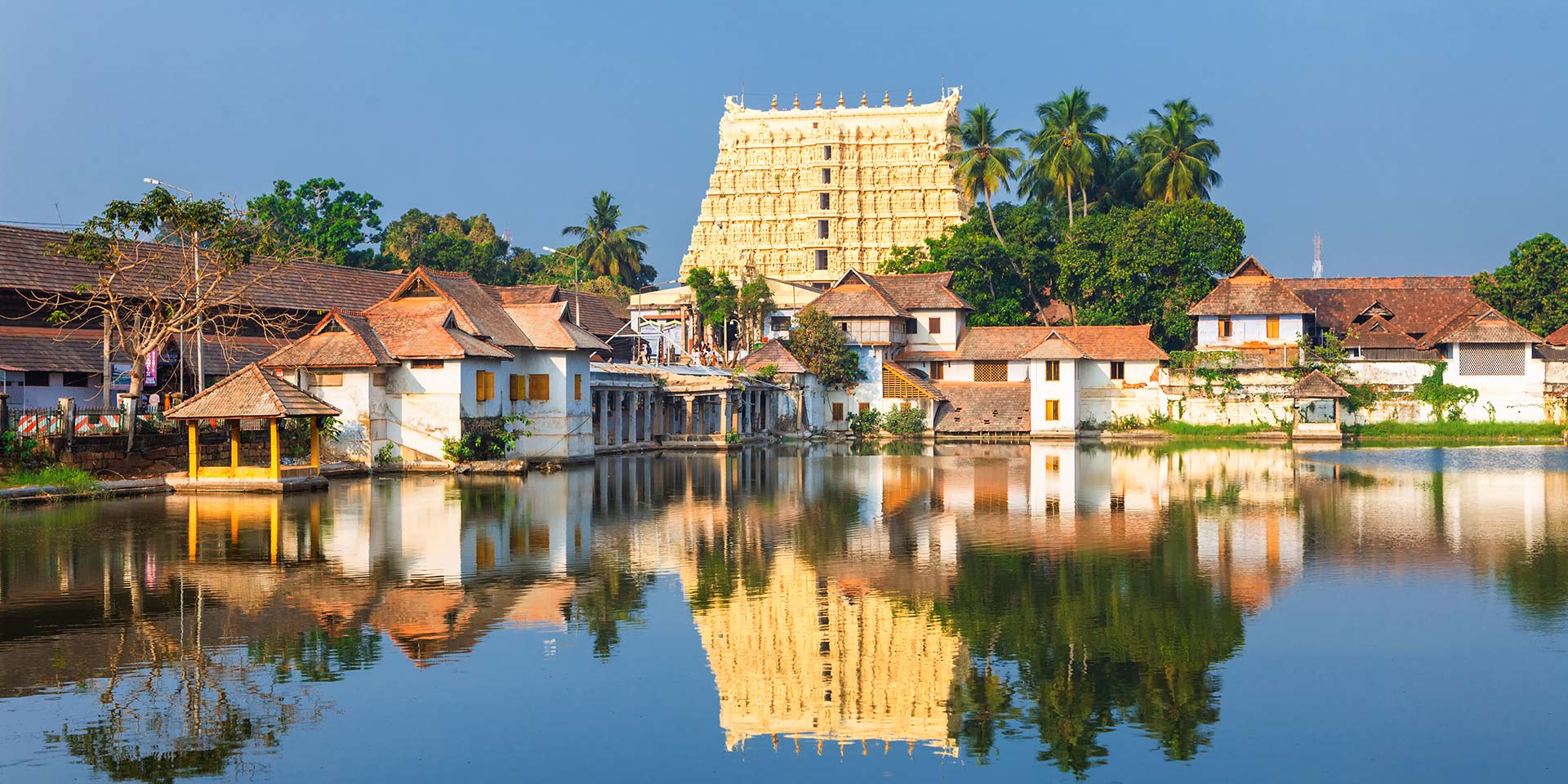

| Modern Somnath temple |

Nuruddin Firoz, a Nakhuda from Hormuz

established a mosque at Somnath in Gujarat in 1264 CE. Two inscriptions–one in

Arabic and the other in Sanskrit–set up to mark this event give us a unique

perspective into the trading world of a rich Persian merchant of the thirteenth

century and his interaction with the host society. In this case, it was

merchants as well as prominent citizens and religious leaders at the famous

Saivite centre of Somnath.

Nakhuda means a ship-owning merchant

(khuda or lord of the ship, nau; nauvittaka in Sanskrit–both the terms started

appearing for the first time around 1000 CE in the context of trade between Red

Sea/Persian Gulf to Western coast of India). Somnath, today, is known mostly

for its sacred character but in the thirteenth century, along with Diu, it was

one of the secondary ports of Gujarat (Cambay/Khambat being the main port).

Nuruddin, who was at Somnath due to some work (not specified in the

inscriptions), purchased the land just outside the city limit, what appears to

be the settlement of the merchants (mahajanapally). The land was purchased from

the temple of Somnath as the mahajanapally itself was the property of the

temple. To provide a regular income to the mosque, he also purchased another

piece of land (this time inside the city and purchased from the Bakulesvara

Temple and negotiated by two priests from two other temples), a few shops in

the market, and an oil mill. The entire transaction was facilitated by a group

of leading merchants of Somanth–all Hindus as their names are mentioned in both

the inscriptions. The most prominent among these merchants was Shri Chada, who

was described as Nuruddin’s dharmabandhav or righteous friend in the Sanskrit

version. The entire transaction was ratified by the town council, Panchakula,

headed by the great Pasupata priest Virabhadra, before being ratified by the

local representative of the Chaulukya King.

The language used in the Sanskrit

inscription, which is also the longer one with full details, shows familiarity

with Islam as it describes the mijigiti (masjid) as a place of worship,

festivals of baratisab (Sab-e-barat) and khatamaratri (whole night recitation

of Koran–both festivals considered important for ship-owners and shipmen) and

the jamat or the congregation at Somnath (interestingly apart from the foreign

merchants and shipmen, it consisted of lime workers, oilmen, etc). The language

is also remarkably similar to donative inscriptions at Hindu/Jaina temples and

even some of the epithets used for Allah actually remind one of Shiva (Viswarupa

and Viswanatha; also Sunyarupa). So, here is the story of a Muslim ship owning

merchants from Hormuz constructing a mosque at a sacred Saiva site with active

help from his Hindu merchant friends on a piece of land purchased from the

temple of Somnath itself. This in a microcosm encapsulates the tolerant,

multicultural, and cosmopolitan trading world of India’s western seaboard in

the thirteenth century. The most remarkable aspect of the whole business was

complete absence of any malice or antagonism towards a Muslim merchant even at

Somnath, which was devastated and desecrated two centuries ago by Sultan Mahmud

of Ghazni. In another thirty years, Alauddin Khilji would conquer and annex

Gujarat, and there would be another round of devastation at Somnath itself.

Gujarat was a curious case where time

and again the rulers fought with the Arabs or the Turks on sea and land but

always welcomed Muslim merchants. In an instance quoted by a contemporary

Muslim writer, Chaulukya King Siddharaja (thirteenth century) himself went in

the disguise of a trader to Cambay to probe an incident of attack on a mosque.

Once satisfied with their claim, he granted the Muslims of Cambay compensation

to rebuild the mosque and also ordered guilty to be punished. Though we, at

times, hear of the presence of Indian merchants in ports of Siraf, Hormuz or

Aden, there were perhaps very few merchants like Jagadu, who maintained his own

agents in all major ports abroad. Overall dominance of Arab traders was so

overwhelming in the Western sector that perhaps in states like Gujarat or

Kerala, there was no option but to welcome them.

|

| Bohra Men |

Apart from the mainstream Sunni

Muslims, Gujarat is also the original home for a number of smaller, often Shia

Muslim sects. The term Bohra itself originated from Gujarati Vehru meaning

trade. The language spoken by more than one million Dawoodi Bohras across the

world (mainly in Western India, Karachi, East Africa, and the USA and Canada)

is essentially a dialect of Gujarati with a large number of loan words from

Arabic, Persian, and other languages. Their religious headquarters, dawat, has

been located in India since the seventeenth century. Bohra men, always attired

in their distinctive white dress, are mostly traders and naturally their

headquarters has always been at a mercantile centre–Ahmedabad, Surat, and now

Mumbai. They have always placed high premium on education and equal

participation of women (in recent times, they have opened community kitchens in

Mumbai to supply meals twice a day to all Bohra families to free their women

from daily chores). However, unfortunately they remained the only community in

India to still practice female genital mutilation–a vestige of their North

African origin.

|

| Present Aga Khan |

The Khojas (from Persian Khwaja or

honourable gentleman) were converts from the Hindu Lohana caste. Though they

have always been part of the Ismaili Shia traditions, they have also preserved

their Hindu pasts. Some of their earlier spiritual leaders took Hindu names to

attract more followers, their belief system closely resembles Vaishanvite

thoughts with their main religious text Dasavatar, celebrating Vishnu’s avatars

along with Ali. However, since the arrival of Aga Khan (originally Imam of

Nizari Ismailis) to India in the nineteenth century and Aga Khan’s emphasis on

Ismaili identity, these beliefs have been in retreat.

Bohra, Khoja, and other such

communities in their foundational myths, always refer to Pirs coming from the

West as the starting point of their faith. Trading links are clearly

discernible in the emergence of these communities. All of them were initially

connected with the Shia Fatimid Caliphate that ruled Egypt from 909 to 1171 CE

from Fustat or Old Cairo. Destination of exports from Gujarat was Egypt

(Cairo/Alexandria, from where Venetian or Genoese merchants took spices and

textiles to Europe), though often the gateway was Aden. Local converts in India

came from the Hindu trading castes such as Lohana, thus they still maintain

similar business ethos and inheritance laws, which prohibit too much division

of family wealth (many of these communities are still legally governed by the

Hindu laws of inheritance).

What exactly prompted them to change

their faith is perhaps difficult to answer and would vary from individual to

individual but the obvious connection was trading links. In a rare first-hand

account, Buzurg bin Shahriyar, maritime merchant and author of the tenth

century Ajabul Hind wrote about his meeting at a Gujarati port with a Hindu

Pilot, who had recently embraced Islam and amassed wealth by piloting ships.

For more such stories related to Indian

business history, see Laxminama: Monks, Merchants, Money and Mantra by Anshuman

Tiwari and Anindya Sengupta Bloomsbury 2018